China's Birth Rate Is Falling. The Economic Shift Is Already Here.

I was reading a Financial Times report the other night, and one number stopped me mid-scroll.

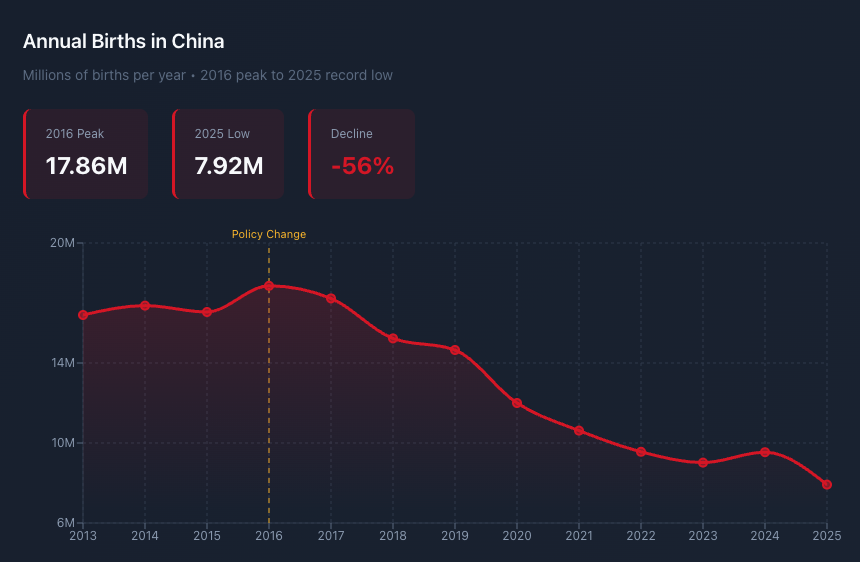

In 2025, China recorded just 7.9 million births. The lowest since records began in 1949. Fewer births than many countries with a fraction of China’s population. I sat with that for a minute. Then I poured another cup of coffee and sat with it some more.

Because this isn’t a slow-moving demographic headline. It’s not a problem for 2050. It’s an economic force already reshaping decisions inside factories, boardrooms, and capital markets. Right now. While most of us are still debating whether AI will take our jobs.

Here’s the tension worth understanding: China’s population is shrinking, yet it remains one of the world’s most critical manufacturing engines. Those two facts don’t contradict each other. They explain each other.

China isn’t waiting for demographics to turn around. It’s building a different kind of economy. One that doesn’t need the workers it’s no longer producing. Industrial robots. Smart factories. AI-driven logistics. This isn’t a futuristic bet. It’s a practical response to a math problem that’s already here. Automation buys time. It preserves scale. And it keeps China relevant in global supply chains even as the workforce contracts.

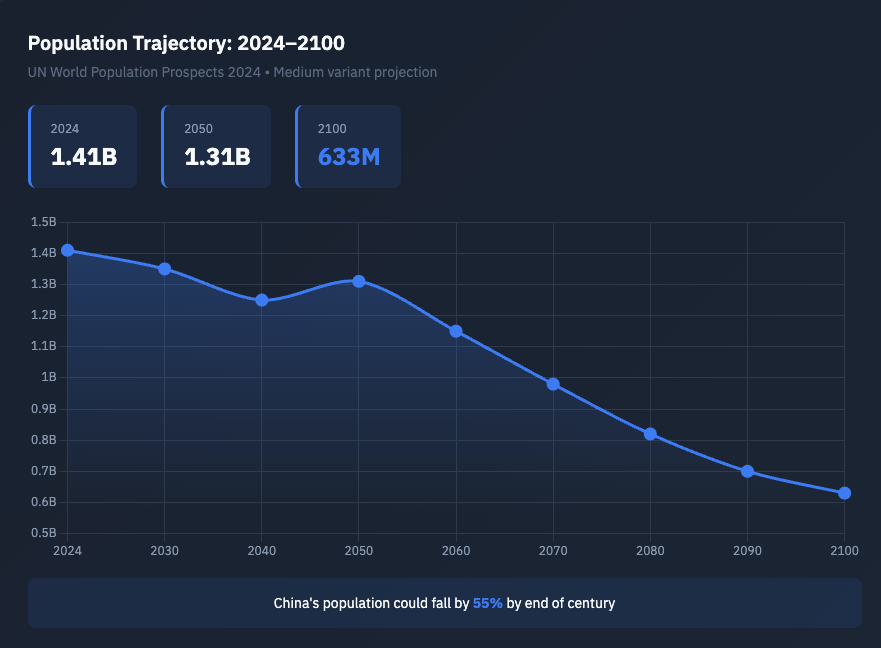

Zoom out further and the strategy comes into focus. The UN projects China’s population will fall from roughly 1.4 billion today to around 1.3 billion by 2050, with steeper declines after that. Some models suggest the population could fall below 650 million by 2100. Fertility has dropped to about one child per woman. Far below replacement level. Those aren’t just statistics. They’re a signal about what kind of economy makes sense going forward.

Labor-heavy growth becomes harder to sustain when there’s less labor. So China is pivoting. Aggressively. Toward industries that run on capital, technology, and productivity rather than young backs and busy hands. Electric vehicles. Batteries. Renewable energy. Biotech. Advanced manufacturing. AI infrastructure. These aren’t random bets. They’re the logical answer to a demographic question most countries haven’t even started asking.

For investors, this is where it gets interesting.

A shrinking population doesn’t mean shrinking opportunity. It means opportunity moves. The question isn’t “will China grow?” It’s “where does capital flow when a country bets on machines over cradles?”

Follow that thread and you land in automation, industrial software, healthcare technology, elder care. Sectors that thrive when workforces age and contract. Meanwhile, industries built around cheap labor or rapid household formation face a longer, quieter pressure. Not collapse. Just gravity.

The mistake is treating China’s birth decline like a sudden shock. It’s not. It’s a slow, structural turn. The kind markets rarely wait for. Capital moves toward where the puck is going, not where it’s been.

China’s demographic transition will unfold over decades. But the economic pivot it’s forcing? That’s already underway. Factories are retooling. Investment is reallocating. Policy is adjusting.

The real question isn’t whether China will change. It’s whether we’ll notice the turn before we’re looking at it in the rearview mirror.

Sources: China National Bureau of Statistics, Financial Times, United Nations World Population Prospects 2024, Our World in Data.